|

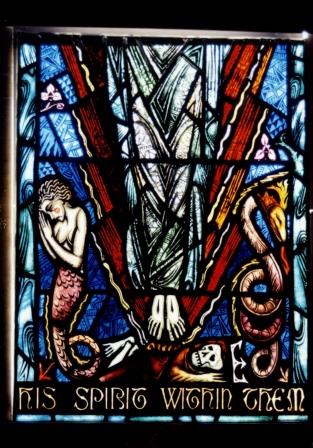

Charles J. Connick was arguably one of the most outstanding stained glass artists of the twentieth century. He first came to the art of stained glass during the opalescent heyday in America. After what he later deemed an embarrassingly long foray working in that manner, he converted to a Gothic-inspired method, of which he became an ardent champion. A favorite of Ralph Adams Cram, one of the most prolific and influential architects of his generation, Connick created distinguished windows in the Modern Gothic style. Although profoundly influenced by the principles he derived from the study of medieval architecture, history, materials, and style, Connick did not see himself as a revivalist but as anchored in the twentieth century and committed to modernity. Throughout the course of his career, Connick was well aware of current artistic trends and integrated new stylistic ideas into his work. Strong linear design and graphic geometry entered his windows in the 1920s and 1930s and, in addition, Connick adopted the use of non-traditional materials in the later 1930s, namely the new acrylic resins. As a result a number of his works can be seen as distinctly experimental, such as the Ocelot window of Lamson & Hubbard’s Boston storefront, the Saint George sample/exhibition panel, and the New England Fantasy window. Each will be discussed in this article alongside the cultural environment influencing its production. A brief introduction Charles J. Connick was born on 27 September 1875 in Springboro, Pennsylvania, one of eleven recorded children of George and Mina Connick, who moved their family to Pittsburgh in 1883 (VIEW HERE).1 During his childhood the family struggled; his father was often unemployed, making it necessary for Connick to drop out of high school to help support his family.2 Throughout his adolescent years he worked as a chalk plate engraver at the Pittsburgh Press and illustrated greeting cards with texts written by his mother.3 In 1894 after making sketches of a sporting event for The Pittsburgh Press, Connick was approached by Horace J. Rudy of Rudy Brothers stained glass studio.4 Rudy identified Connick as a fellow artist, which flattered the then nineteen-year-old youth, who agreed to accompany Rudy to his studio.5 Recalling the moment when the gas lamps were lit, revealing the glinting stocks of glass sheets, Connick claimed he was transported into a ‘wonderland of glassiness.’6 Rudy offered Connick an apprenticeship to help finish a large commission, which he fervently accepted, staying on with the Studio to continue this new ‘adventure in light and color.’7 Connick’s time there coincided with a reduction in commissions, so Rudy helped Connick secure work at other studios.8 Throughout these years and subsequently after leaving Rudy Brothers, Connick worked as a designer with various firms in Pittsburgh, Boston and New York, including: Conroy, Prugh & Company, where he worked as a manager; Spence, Moakler, and Bell; Horace J. Phillips and Company; Vaughan and O’Neill; Tiffany Studios, though briefly; and probably Willet Studios.9 Later, he returned to Rudy Brothers as Art Director.10 His first independent commission came in 1909 in the form of the George H. Champlin memorial window for All Saints Church in Brookline, Massachusetts.11 This commission allowed him to quit his current job and to work as an independent contractor out of the Boston studio of Arthur Cutter.12 This was also Connick’s first collaboration with architect Ralph Adams Cram.13 Cram became the most influential supporter of Connick’s work, commissioning him whenever possible to create windows for his own buildings.14 Finally in 1913, Connick was able to open his own stained glass studio at 9 Harcourt Street in Boston’s Back Bay, where he produced a substantial body of distinguished work until his death in 1945 (VIEW HERE).15 Art Deco and the 1925 Paris Exposition Art Deco, a style emphasising geometry and linear pattern, acquired its name from the 1925 International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts which took place in Paris, France. Held during the pinnacle of enthusiasm for world’s fairs, the exhibition showcased the best examples of contemporary art and technology of participating countries – although the United States was not among these. However, Connick was appointed by the US Secretary of Commerce to visit and report upon the exposition and therefore attended as part of the United States Commission; as such he wrote ‘Appendix A: Stained Glass’ for the official report.16 After this experience, Art Deco tendencies began to show in his work, which although remaining decidedly Gothic in overall nature, now took on a new degree of geometric and linear design (FIG. 1 at Bottom). In an article originally printed in the New York Times Magazine, Connick recorded that the 1925 Paris Exposition ‘revealed an exuberant spirit in all crafts’ and the ‘experiments shown there shocked many designers and craftsmen from the orthodox shops and factories of America.’17 Connick verbally illustrated the glass showcased, giving us an idea of the ‘bizarre arrangement in iron, lead and glass in chunks and in bulging built-out sections that marks the doorway of the Lafayette pavilion’ (perhaps an early version of dalle de verre) which can be seen in the Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs’ photograph (VIEW HERE).18 Connick also described the ‘cubist decoration’ of the building devoted to Transport and Tourism, and the unsuccessful enamelled windows that ‘have already begun to peel off,’ after only one year in the church at Rancy.19 Despite a previous dislike for etching and cutting on plate glass, Connick expressed astonishment at the success of the examples provided by the French artists.20 It was with this new style of etched plate glass fresh in his mind that Connick went into his commission for the storefront of the new building for Boston furriers, Lamson & Hubbard. The Lamson & Hubbard Storefront Although Connick was, arguably, influenced by Art Deco in his other windows of the period, such as the Christian Epic windows in Princeton University’s chapel (FIG. 1 at Bottom) and the windows of St Gabriel’s Catholic Church in Washington, DC, his embrace of etched glass for this commission was a strong departure. Connick Studios embarked on the Lamson & Hubbard storefront commission in 1929 after multiple requests for ‘the type of ornamental glass which has recently been developed in France and in this Country; that is, the method of etching or chipping patterns on plate glass, and these patterns possibly enriched with gold, silver or color.’21 For the storefront, Connick designed the windows and made cartoons, and collaborated with the Eny Art Glass Company of New York City who manufactured the etched windows (Image to come).22 Art Deco sympathies are evident. The bold, angular lines and stylised imagery seen throughout the Lamson & Hubbard storefront represent this new type of design (Image to come). An Ocelot is shown crouching in profile at the center of a cartouche, which in turn is centered in a square panel of glass (VIEW HERE). The strong geometric patterns in the sawtooth border of the square panel, the bold brick-like pattern surrounding the ocelot, and the modified fret or key pattern on which the ocelot stands all reveal the impact of Art Deco, and the strong outlines and stylisation add to the flattened appearance of this etched window. The minimal color palette – the majority of the window is colourless – along with the wide white borders, recalls the new type of etched glass shown in Paris. Based on letters from Connick to the Eny Art Glass Company and Peter Andre, Inc., it is evident that he likely found his inspiration in the etched glass windows he had seen at the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts.23 A comparison with The Leopard, a window created by Gaëtan Jeannin in collaboration with Eric Bagge, reveals what may be seen as a direct influence on the storefront design (VIEW HERE, PAGE 26 OF TEXT).24 Connick himself acknowledged that the commission was ‘somewhat of an experiment.’25 The use of plate glass and etching and the collaboration with an outside company were all unusual for the Studio. Despite the challenges required, and the multiple changes and improvements needed to adapt to the new medium, Connick recounted that he was ‘beginning to see excellent possibilities in such work, and even if this commission should be abandoned, I shall undertake other things of the sort for sympathetic clients.’26 Dalle de verre innovations and exhibitions of the 1930s During the 1920s and ’30s, French glass artists established an innovative technique in glass making, soon known as dalle de verre, which diverged from contemporary methods of stained glass production based on traditional techniques. In this method, chunks of glass – known as dalles or slabs – were inset in cement and strengthened with a wire framework. It is worth noting that this type of architectural glazing resembles an older method of insetting thick chunks of glass in a geometric stone framework, as used throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East; it is possible that the French artists were aware of this historic type of glazing.27 The 1937 Paris World’s Fair was the first time that dalle de verre was exhibited to the public on a large scale, the French Pavilion of stained glass displaying the process of construction and the finest examples of this new medium.28 According to American stained glass artist Joseph Reynolds, such windows were controversial in Paris, polarising opinion between the Academy and those who supported the contemporary style.29 Dalle de verre windows made for the Cathedral of Notre Dame were included in the Roman Catholic Pavilion. Despite their modernity, they had lancets filled in the traditional Gothic manner with single figures of saints surrounded by a wide border.30 Interestingly, the Egyptian Pavilion also included examples of dalle de verre. Although the United States participated this time in the exhibition, their pavilion was poorly designed and crowded. Connick himself included seven medallion windows, including two replicas from the Christian Epic windows at Princeton University Chapel, and five made from glass salvaged from the area around the closed Boston & Sandwich Glass Company.31 In 1939, dalle de verre windows made their way to North America in the work of French-born artist Auguste Labouret. His window One of the Magi, made in 1936, was shown at the New York World’s Fair.32 He also installed what is thought to be the first such window on the continent at the important Shrine of Saint Anne de Beaupré in Quebec, Canada, to which he would eventually contribute over two hundred windows. Labouret was an early pioneer of dalle de verre in France, helping to develop the technique in the early 1930s.33 Saint George Connick spent a considerable amount of time travelling throughout the United States for commissions and also around Europe studying medieval stained glass. He attended and participated in exhibitions and World’s Fairs, and consequently was well aware of any innovation in his craft. It is therefore probable that Connick knew of dalle de verre as both an ancient and modern technique before the 1937 World’s Fair, where he certainly observed the examples on show. In a 1993 interview, Orin E. Skinner, Connick’s ‘left-handed right-hand man,’ said that Connick Studios did some work in dalle de verre but that they did not particularly like it.34 Marilyn B. Justice, President of The Charles J. Connick Stained Glass Foundation, who was present at this interview, agreed but added that the door of the studio actually had dalle de verre glass inset in it.35 The Charles J. Connick Stained Glass Foundation Collection at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology includes a panel reminiscent of dalle de verre (VIEW HERE). The Saint George panel (c.1930-1940) is not known to have been a commission – and based on its small size, just over two feet at the longest – it was probably made as a sample panel and is markedly stylised in its design. It illustrates Saint George sitting atop a white horse, his helmeted head low against the horse’s neck with a red cloak billowing out behind him. In his hand he holds a white shield with a red cross. Entwined beneath the horse’s legs is a dragon, almost imperceptible in its abstraction. All the figures are seen in profile. The leadlines are extremely thick, and opaque black paint visually increases their width. Although the glass is just a flat sheet, it is painted with vitreous paint so as to appear faceted. This panel was apparently an early experiment to create the look of faceted glass (or was it perhaps a reaction against faceted glass?). Skinner’s admission that they did not like the medium may have prompted the mimicking of the style in a medium that the Studio preferred. Whatever the purpose of the St George panel, it is clear that Connick followed innovations in his craft and did not balk at trying them in his own work. Plexiglas and World War II The nineteenth century saw the creation of the first plastics, namely celluloid, Bakelite and a large number of chemically similar products. These plastics could only be moulded one time and were visually opaque.36 Thus the invention of acrylic glass, given the brand names ‘Plexiglas’ by Röhm & Haas Company and ‘Lucite’ by their competitor DuPont Lucite, was revolutionary. Acrylic glass is colourless and transparent, can be made into large sheets and bent into any shape – and importantly, it can be remoulded after being formed.37 In 1939, Röhm & Haas Company had an exhibit designed to showcase Plexiglas and also Crystallite acrylic plastic (the powdered version suitable for moulding), at the World’s Fair in New York.38 The Herman Miller Furniture Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan, included a Plexiglas and tubular steel chair at the fair, the epitome of modern design.39 Plexiglas was quickly embraced by the World War II war effort as the perfect solution for shatterproof windows, canopies, bomber noses and gun turrets in the new high-altitude military aircraft.40 Post-war, Crystallite became the preferred material for headlights, turn signals and taillights for automobiles and Plexiglas became well known through backlit signs, like those of Shell gas-stations, McDonald’s, jukebox windows and movie marquees.41 New England Fantasy During World War II, rationing of everyday materials became the norm and the rationing of metals, namely lead, directly affected Connick Studios. In a 1943 letter to the Bureau of Construction and War Production Board Connick petitioned for the right to use lead that the Studio already owned.42 The lengths to which he had to go to use his own lead, plus the fact that the studio’s younger staff were absorbed by the war effort, leads one to wonder how the Connick studio’s output was affected.43 In fact the lead shortage, coupled with Connick’s own inclinations towards innovation and modernity, spurred him on to try his own experiments in plastic.44 According to Orin E. Skinner, Connick was ‘among the first to try ‘gelva,’ and others of the earliest plastics.’45 Experiments, such as plastic curtain pulls and plastic and glass buttons, culminated in the creation of a full size window, the New England Fantasy (FIG. 2 at Bottom),46 made for exhibition at the Contemporary American Industrial Art Exhibition of 1940 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.47 Skinner later related that the window was ‘a panel of colorful glass imbedded in one of the synthetic resins in sections glazed with zinc cames.'48 The panel was heralded by Glass Digest as a ‘new type of glass, quite different from anything that has been done before,’ and was described by Connick as a ‘Coloralight Mosaic’, with its ‘patent pending’.49 Although the New England Fantasy is not a dalle de verre window as such, it is worth noting that its marriage of acrylic resin and chunks of glass predates by almost twenty years the major technical innovation of epoxy resin as the material to hold the slabs of glass together. Robert R. Benes, working with Jacoby and Frei Studios in New Orleans, is credited with the formulation of a special blend of epoxy to replace the cement in dalle de verre windows around 1960.50 Connick’s brilliant mosaic used the new materials to illustrate Leonora Speyer’s ballad about ‘Old Doc Higgins’, who shot a mermaid. It was representative, according to Connick, ‘of the contests constantly going on between the literal- minded folks and the creatures of the imagination.’51 Doc Higgins inhabits the right side of the panel with the mermaid on the left, both figures facing each other in profile. Waves curl around the mermaid’s tail and the focal point of the window is a brilliant sun at the apex. The sun’s rays project down across the window in angular paths of saturated yellows, oranges and pinks. The colorless transparent quality of the acrylic added to the glowing quality of the panel, for which a light-box with fluorescent illumination was constructed.52 The desire to illuminate with artificial light was part of Connick’s ambition to bring colour and light beyond cathedral walls into factories, offices, schools and any space where it could best serve the public (FIG. 3 at Bottom). In addition to the New England Fantasy window, Connick made a number of ‘Coloralight Medallionets’ which were comprised of the ‘scraps of glass we are using in our great windows, and a new plastic material that is very light and very durable so these little Medallionets can sing forth their messages in the light almost anywhere.’53 An example of such a ‘medallionet’ has been found in the Charles Connick Foundation collection (Image to come). Its misshapen form suggests the sensitivity of the materials to overly warm conditions. In addition to this small example, two others are known from letters. Connick gifted one of them to Florence W. Foss of South Hadley, Massachusetts, who assisted him with a commission at Mount Holyoke College, and the other to Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.54 He also made Kodachrome photographs of the New England Fantasy window to create Christmas cards that further publicised his new invention.55 A Modern Gothicist Charles Connick is considered by many to be the most important Modern Gothic stained glass artist of the twentieth century. In fact, the depth of his knowledge of stained glass, his passion for the creation of stained glass windows and for educating the public through lectures and writings, helped to define the Modern Gothic style of stained glass early in the century. As scholars Peter Cormack and Albert Tannler have pointed out, this was in sharp contrast to the prevailing influence of opalescent windows in America as practiced by Tiffany and La Farge et al.56 Despite Connick’s dedication to the techniques and materials of medieval stained glass, as these authorities have noted, he was not a historicist or a copyist. His drive for constant learning and innovation and his ambitious creativity is apparent through the evolution of his style. This is evident in numerous windows, many considered masterpieces of their time. The case studies presented here further illustrate some of the more unusual examples of Connick’s desire to embrace contemporary trends and experiments, letting nothing stand in his way of creating the very best stained glass of which he was capable. Connick may have been a Gothicist in spirit but he was unquestionably also a Modernist. Perpetual modernness is the measure of merit in every work of art. Charles J. Connick ________ NOTES 1 Joan Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years: Life before Boston,’ Connick Windows (Boston: Charles J. Connick Foundation, February 2000), http://www.cjconnick.org/newsletters/February2000.html; Albert J. Tannler ‘Edward Burne- Jones and William Morris in the United States: A Study of Influence’ The Journal of Stained Glass, Burne Jones-Special Issue 35 (2012), includes analysis of Charles Connick pp. 53-57. 2 Joan Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years’, Connick Windows. 3 Charles J. Connick, Adventures in Light and Color (New York: Random House, 1937), 4; Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years’. 4 Connick, Adventures in Light and Color, 4. 5 Ibid. 6 Ibid. 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid. 9 Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years’; Noreen O’Gara, ‘Retrospective Charles J. Connick,’ Stained Glass Quarterly (Spring 1987): 45; Peter Cormack, ‘Glazing “with Careless Care” Charles J. Connick and the Arts & Crafts Philosophy of Stained Glass,’ The Journal of Stained Glass 28 (2004): 82. 10 Ibid. 11 O’Gara, ‘Retrospective’, 45. 12 Ibid. 13 Ibid. 14 Ibid. 15 ‘History of the Connick Studio’, The Charles J. Connick Foundation, http://www.cjconnick.org/studio-history/. 16 Charles J. Connick, ‘Appendix A: Stained Glass.’ Report of Commission appointed by the Secretary of Commerce to visit and report upon the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Art in Paris, 1925. 17 Charles J. Connick, ‘Modern Stained Glass at the Paris Exhibition, 1925,’ The Journal of Stained Glass 2 (1927), 12. 18 Connick, ‘Appendix A.’ 19 Ibid. 20 Connick, ‘Modern Stained Glass,’ 16. 21 Letters to Peter Andre, Inc. and the Eny Art Glass Company, 19 March 1929, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 22 Memos, 16 November 1929 and 3 December 1929, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 23 Letters to Peter Andre, Inc. and the Eny Art Glass Company, 19 March 1929. 24 Jacques Gruber, Le Vitrail a L’Exposition Internationale Des Arts Decoratifs Paris 1925 (Paris, France: Editions Charles Moreau, 1926), fig. 26. 25 Letter to Theophile Schneider, 8 May 1930, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 26 Letter to Theophile Schneider, 30 July 1929, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 27 ‘History of Stained Glass’ Stained Glass Association of America. Accessed 12 May 2014, http://stainedglass.org/?page_id=169 28 ‘Modern Stained Glass at Paris Exposition Discussed by Joseph G. Reynolds, R. Boston Craftsman,’ Reel 3, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 29 Ibid. 30 Ibid. 31 Glass Digest (1937), Charles J. Connick file, Rakow Library, Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. 32 ‘History of Stained Glass’, Stained Glass Association of America. 33 Ibid; ‘Stained Glass’, Sanctuaries-Shrine Sainte-Anne De-Beaupré. Accessed 12 May 2014. http://www.sanctuairesainteanne.org/index.php?option=com_zoo&view=item&layout=item&It emid=201&lang=en 34 Richard Hoover, ‘Behind the Scenes: Conversing About Stained Glass with Orin E. Skinner,’ Stained Glass 98 (Summer 1993), 109. 35 Ibid. 36 Jason T. Busch and Catherine L. Futter, Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs, 1851-1939 (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012), 30. 37 Ibid. 38 Ibid. 39 Ibid. 40 Ibid., 42. 41 Busch and Futter, 32; also ‘Leading the Way From 1933 to 2008,’ Altuglas International Arkema Group, accessed 24 March 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20120905160256/http://www.plexiglas.com/home/aboutus/timeline _content 42 Letter to the Bureau of Construction, 10 June 1943, Church Street Church, Knoxville, Tennessee file, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 43 Ibid. 44 Virginia S. Bright, ‘Interview with Charles J. Connick May 10, 1945,’ Reel 2, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 45 Orin E. Skinner, ‘An Autobiography,’ Stained Glass 72 (1977-78), 234; Orin E. Skinner, ‘Connick in Retrospect,’ Stained Glass (Spring 1975), 18. 46 Skinner, ‘Connick in Retrospect,’ 18. 47 ‘ “New England Fantasy” Coloralight Mosaic by Connick of Boston,’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gelva, New England Fantasy, New York City file, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art Contemporary American Industrial Art 1940, 15th Exhibition (29 April 29-15 September 1940), 25. 48 Skinner, ‘Connick in Retrospect,’ 18. 49 Glass Digest (June 1940), Charles J. Connick file, Rakow Library, Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York, ‘‘New England Fantasy’ Coloralight Mosaic by Connick of Boston,’ 25. 50 ‘History of Stained Glass’, Stained Glass Association of America; ‘History of Jacoby Stained Glass Studios, Inc.,’ Jacoby Art Glass Company, St Louis, MO, accessed 27 March 2013, http://tropicalsails.com/jacobyoppliger/; Oppliger, William, and Stephen Frei, ‘Jacoby Art Glass Company’, ‘Christ Church Bluefield,’ accessed 13 May 2014, http://www.cecblf.org/jacoby.html 51 ‘‘New England Fantasy’ Coloralight Mosaic by Connick of Boston,’; letter to Mr and Mrs Fuller, 20 December 1941, Reel 1, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 52 Ibid. 53 Letter to Miss Foss, 10 April 1940; letter to Mr and Mrs Fuller, 20 December 1941, Reel 1, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 54 Ibid. 55 Letter to Brother Yeomans, 20 December 1941; letter to Mr and Mrs Fuller, 20 December 1941, Reel 1, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 56 Peter Cormack, ‘Glazing “with Careless Care” Charles J. Connick and the Arts & Crafts Philosophy of Stained Glass,’ JSG 28 (2004): 79-94; Albert J. Tannler, Charles J. Connick: His Windows in and Near Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation, 2008). This article was published by the Journal of Stained Glass, the scholarly journal of the British Society of Master Glass Painters, to whom I am most grateful.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ArchivesSamantha

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed