|

Setting the Stage

Stained glass in the late nineteenth century was influenced by a variety of factors—moral, theological, and political. These factors dictated the amount and style of the stained glass produced, as well as the artists making it. By this time, England’s Industrial Revolution was well underway and opposed by various intellectual groups whose romantic viewpoint of the pre-industrialized world, particularly that of the Middle Ages, lead to what is deemed the Romantic Period. These intellectuals portrayed the Middle Ages as an era of simplicity and morality, and represented these ideals both in art and literature. Simultaneously religious theory underwent great changes, with two organizations at the forefront: the Tractarians of the Oxford Movement, a theological organization based at Oxford University, and the Ecclesiologists of the Cambridge Camden Society, an architectural society based out of Cambridge University. These organizations fought to strengthen liturgical rituals and elaborate ecclesiastical interior and exterior architecture, including stained glass. The ideologies and actions of the Romantics, Tractarians, and Ecclesiologists were inadvertently supported by legislation encouraging the increased construction of Anglican churches within the United Kingdom, resulting in increased demand and production of stained glass in Victorian England. Political Background During the nineteenth century British authorities began to worry about the state of the English Church. The population of England exceeded the available seating in Anglican churches by around two and a half million people. In the eyes of the English, a lack of religious participation was connected to revolution: the French Revolution (1789-99) was partially driven by anti-clericalism, the overthrow and death of Charles I of England was influenced by Nonconformity (rebellion against the Anglican Church), the 1798 rebellions in Ireland were religion driven, and even the American Revolution was influenced by religious motives—in the eyes of the English. Officials were afraid of the consequences of unavailable seating, and as a result, legislation was put in place between 1803 and 1824 that mandated the construction and repair of Anglican churches. In 1860 alone 7,500 new churches were built, and by 1880 that number rose to 16,000. These new churches would, in the eyes of the monarchy and Parliament, keep dissent from the Anglican Church from growing, as well as ensure the moral and religious future of the people, seventy-five percent of whom currently failed to attend regular religious services. Oxford Movement It was during this period of moral concern that the Oxford Movement, a theological movement comprised of the High Churchmen within the Anglican Church, became active. The High Churchmen of this movement (who became known as the Tractarians after their publication The Tracts for the Times) felt the Anglican Church had become too secular, the state held too much control over it, and it had lost touch with its roots in the pre-Reformation church (really meaning its Roman Catholic lineage). The Tractarians argued that the Anglican Church was part of and retained an unbroken connection with the Roman Catholic Church, and began to look towards it as the best model for Church of England (the Anglican Church in England). They were concerned with the liturgical rituals of church services. They moved for deeper worship, more frequent celebrations of the Eucharist, and a stronger view of the clergy—all themes of the Roman Catholic Church and a large departure for the Anglican Church, which was established after the rejection of these practices during the Reformation. To begin this new reform some Anglican churches abandoned the Book of Common Prayer for the Roman breviary and missal. Additionally Latin services were incorporated into worship, and the service began to follow Roman Catholic liturgical devotions more closely. This desire to strengthen the connection between the Anglican and Roman Catholic Churches was a staple to the Oxford Movement’s theology, and very controversial. Prejudice against Roman Catholics was very strong during the nineteenth century. The Low Churchman (the opposing group in the Anglican Church) became suspicious that the High Churchmen were crypto-Papists (Papist being a slur against Roman Catholics) or even Catholic spies. Catholicism was also associated were the “undesirable” places in Europe—Ireland and France for example—and thus, all things combined, encouraged anti-Papal riots against a fear of Papal aggression. Cambridge Camden Society Simultaneously the Cambridge Camden Society was established (1833) at Cambridge University to take on the role of reviving church architecture. The Ecclesiologists (as they became known, after their publication The Ecclesiologist) followed A.W.N. Pugin’s (1812-52) example towards a purer use of the Gothic influence in church architecture, compared to that which had been used in the previous two centuries. They built new churches and restored old ones in a manner that captured a romantic vision of the Middle Ages, creating the physical manifestation of the Tractarian’s theology. They were the driving force behind the Gothic Revival in both exterior and interior ecclesiastic architecture. For example, all forms of ritualistic objects—chancels, vestments, even use of the Cross—were regarded with skepticism and thought of as highly Catholic by the Anglicans, particularly the Low Churchmen, but championed by the Ecclesiologists. The Low Churchmen argued that all symbolist, ceremony, sacred imagery, and decoration associated with the Roman Catholic Church were unacceptable for use in the Anglican Church. Despite this, many Anglican churches, encouraged by the Ecclesiologists, began embracing the splendor promoted by Gothic Revivalists, including carved pinnacles, tiled roofs, detailed metalwork, vestments, and stained glass windows. Interiors became so decorated that some churches had to put out a sign letting people know that they were in fact not Roman Catholic. The Ecclesiologists promoted their ideas on church buildings and the revival of gothic influence through their journal, The Ecclesiologist. They used it to scold the public for their neglect of their country’s churches, while keeping their own homes comfortable and maintained. They also used it as a platform to explain the purposes of all the trappings of medieval churches, which were now showing up in their Anglican churches, and which most people in Britain were ignorant and suspicious of, since they were so closely related to the objects and architecture of the Roman Catholic Church. The Ecclesiologist became a sort of handbook for the Gothic Revival. It embraced Pugin’s ‘true principles’ (The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture, 1841) and adopted the Decorated Style (a division of English Gothic architecture dating around 1250 to 1350) as the approved style for church architecture. Stained glass was discussed with enthusiasm and serious consideration in The Ecclesiologist, which strongly encouraged its revival. A.W.N. Pugin and Stained Glass Like everything else, the Ecclesiologists had strong opinions about which stained glass was worthy of reproduction in the new gothic revival churches. The figurative focus of eighteenth-century stained glass, which was treated more like a canvas, painted heavily with enamels, resulted in dark glass that did not actually function as a window. Medieval glass was preferred for the vibrancy of color, harmony of materials, and serious and religious nature, all of which were lacking in the eighteenth-century windows. Early in the Ecclesiologists’ popularity, copying of medieval windows, almost directly, was encouraged as a way to learn the art. Later this practice became a stepping stone to a more contemporary translation of the windows, which pulled from a variety of influences. Through The Ecclesiologist the High Churchmen lectured on the best styles to imitate and the best architects and craftsmen to hire, and they could make or break the fate of an architect as a result of their reports. A.W.N. Pugin was one of the early leading figures in the Gothic Revival. He established the basis for archaeological accuracy and set the highest standards for the recreation of medieval principals in English stained glass production. He laid out the standards for good design, which was a result of his opinions on the demise of stained glass following the Middle Ages. He felt there were three reasons for this demise: the decline in gothic architecture, which was the only style that would exhibit stained glass to its full effect; the rendering of stained glass as complete pictures in the sixteenth century, which had no union with the architecture surrounding it; and the discovery of a new process of enameling in the seventeenth century leading to an overuse of enameling, which corrupted the translucency of the glass. To ensure future good design, Pugin wrote The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture, which provided his guidelines for both architectural and stained glass design. His book was revered by all in the field and is still an important resource today. Pugin, who in addition to being an art critic was also an architect and designer, designed stained glass for his own churches. Over the years he worked with a variety of craftsmen until he formed a partnership—with John Hardman of Birmingham—that gave him complete creative control. Prior to this partnership Pugin hired William Warrington, a virtually unknown pupil of Thomas Willement, to make his first windows in 1838. By 1842, Warrington became too expensive for Pugin to retain, and he began working with William Wailes. Although Wailes created high quality stained glass, what Pugin really wanted was complete creative control that resulted when he convinced his friend Hardman to expand his already established workshop to include stained glass production, under Pugin’s direct supervision. Renamed as John Hardman & Company, they would set the precedent for all stained glass by 1850. For the first four years, Pugin designed virtually all the stained glass, which was made for his own churches. Pugin’s personal preference was for Early, Decorated, and Late Gothic period glass, from between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. His windows were not mere copies, but rather used medieval principles of building to create windows that were new works of art. Eventually, he and Hardman began working with white glass; silver stains; more lighthearted colors; varying poses, gestures, and expressions; and livelier draperies. He also moved away from canopied windows towards the use of quatrefoil shapes. In the late 1850s grisaille glass also became a predominate feature of Pugin’s and Hardman’s windows. By 1849 his work had moved beyond his own Roman Catholic churches to be featured by architects of the Anglican churches, including those of William Butterfield and George Gilbert Scott. Between 1851 and 1856, John Hardman & Company, along with William Wailes, was the most favored stained glass producer within Ecclesiological circles. In the late 1850s the firm of Clayton & Bell began gaining popularity as well. Clayton brought a Pre-Raphaelite influence from his friendship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti to their work, which inspired him to work in a freer, less serious manner. Clayton began designing stained glass in 1853, and had originally worked under Richard Cromwell Carpenter, one of the Ecclesiologists’ favorite architects, which lead to an early and enthusiastic acceptance of his work. The Ecclesiologist highly praised Clayton & Bell’s work at Westminster Abbey, and their renovation of St. Michael’s in London was called the best work that any English stained glass artists had yet produced since the revival of the art. Negative Effects of the Church Boom on Stained Glass Gothic Revival stained glass production is inherently entwined in the great demand for church construction in nineteenth-century England, and as a result this great demand affected the physical production of these windows. For example, and noted by architect George Gilbert Scott, Clayton & Bell’s early, imaginative choices and numerous color ranges begin to become diluted by the 1860s when they begin to use harder, more metallic colors in standard red, blue, and white. Bell abandons his iconic use of canopy work after the 1860s as well. Such a lack of detail suggests that Clayton & Bell were not as involved in production, doing little more than approving the initial sketches. Pressure to produce stained glass quickly and in great quantity caused many studios to struggle to keep up with demand and resulted in a decrease in stained glass quality. Conclusion The success and revival of stained glass during the nineteenth century was, to a great extent, a product of the theological push towards High Churchmanship inspired by the Oxford Movement and physically manifested by the Ecclesiologists. Stained glass was considered vital for the creation of the awe inspiring feeling the High Churchmen wanted to invoke for congregations—a romantic look back to worship in the Middle Ages. Although the politically provoked boom in church construction inspired the revival of stained glass production, it was the Tractarians and Ecclesiologists played an essential part in ensuring that the stained glass produced met intellectual and aesthetic standards of design. _________________________ Suggested Reading Atterbury, Paul and Clive Wainwright. Pugin A Gothic Passion. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994. Brisac, Catherine. A Thousand Years of Stained Glass. London and Sydney: Macdonald & Co., 1984. Cheshire, Jim. Stained Glass and the Victorian Gothic Revival. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2004. Curl, James Stevens. Book of Victorian Churches. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd/English Heritage, 1995. Faught, Brad C. The Oxford Movement, A Thematic History of the Tractarians and Their Times. Philadelphia, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2003. Harrison, Martin. Victorian Stained Glass. London, Melbourne, Sydney, Auckland, Johnannesburg: Barrie & Jenkins, 1980. Scott, Sir George Gilbert. Personal and Professional Recollections. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivingtong, 1879. Yates, Nigel. Buildings, Faith, and Worship 1600-1900. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

0 Comments

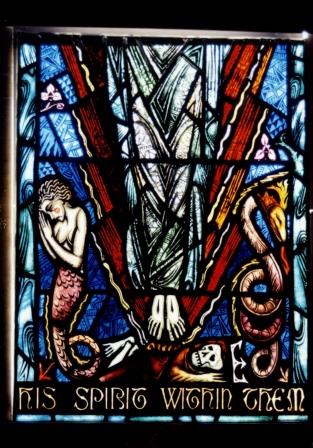

Charles J. Connick was arguably one of the most outstanding stained glass artists of the twentieth century. He first came to the art of stained glass during the opalescent heyday in America. After what he later deemed an embarrassingly long foray working in that manner, he converted to a Gothic-inspired method, of which he became an ardent champion. A favorite of Ralph Adams Cram, one of the most prolific and influential architects of his generation, Connick created distinguished windows in the Modern Gothic style. Although profoundly influenced by the principles he derived from the study of medieval architecture, history, materials, and style, Connick did not see himself as a revivalist but as anchored in the twentieth century and committed to modernity. Throughout the course of his career, Connick was well aware of current artistic trends and integrated new stylistic ideas into his work. Strong linear design and graphic geometry entered his windows in the 1920s and 1930s and, in addition, Connick adopted the use of non-traditional materials in the later 1930s, namely the new acrylic resins. As a result a number of his works can be seen as distinctly experimental, such as the Ocelot window of Lamson & Hubbard’s Boston storefront, the Saint George sample/exhibition panel, and the New England Fantasy window. Each will be discussed in this article alongside the cultural environment influencing its production. A brief introduction Charles J. Connick was born on 27 September 1875 in Springboro, Pennsylvania, one of eleven recorded children of George and Mina Connick, who moved their family to Pittsburgh in 1883 (VIEW HERE).1 During his childhood the family struggled; his father was often unemployed, making it necessary for Connick to drop out of high school to help support his family.2 Throughout his adolescent years he worked as a chalk plate engraver at the Pittsburgh Press and illustrated greeting cards with texts written by his mother.3 In 1894 after making sketches of a sporting event for The Pittsburgh Press, Connick was approached by Horace J. Rudy of Rudy Brothers stained glass studio.4 Rudy identified Connick as a fellow artist, which flattered the then nineteen-year-old youth, who agreed to accompany Rudy to his studio.5 Recalling the moment when the gas lamps were lit, revealing the glinting stocks of glass sheets, Connick claimed he was transported into a ‘wonderland of glassiness.’6 Rudy offered Connick an apprenticeship to help finish a large commission, which he fervently accepted, staying on with the Studio to continue this new ‘adventure in light and color.’7 Connick’s time there coincided with a reduction in commissions, so Rudy helped Connick secure work at other studios.8 Throughout these years and subsequently after leaving Rudy Brothers, Connick worked as a designer with various firms in Pittsburgh, Boston and New York, including: Conroy, Prugh & Company, where he worked as a manager; Spence, Moakler, and Bell; Horace J. Phillips and Company; Vaughan and O’Neill; Tiffany Studios, though briefly; and probably Willet Studios.9 Later, he returned to Rudy Brothers as Art Director.10 His first independent commission came in 1909 in the form of the George H. Champlin memorial window for All Saints Church in Brookline, Massachusetts.11 This commission allowed him to quit his current job and to work as an independent contractor out of the Boston studio of Arthur Cutter.12 This was also Connick’s first collaboration with architect Ralph Adams Cram.13 Cram became the most influential supporter of Connick’s work, commissioning him whenever possible to create windows for his own buildings.14 Finally in 1913, Connick was able to open his own stained glass studio at 9 Harcourt Street in Boston’s Back Bay, where he produced a substantial body of distinguished work until his death in 1945 (VIEW HERE).15 Art Deco and the 1925 Paris Exposition Art Deco, a style emphasising geometry and linear pattern, acquired its name from the 1925 International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts which took place in Paris, France. Held during the pinnacle of enthusiasm for world’s fairs, the exhibition showcased the best examples of contemporary art and technology of participating countries – although the United States was not among these. However, Connick was appointed by the US Secretary of Commerce to visit and report upon the exposition and therefore attended as part of the United States Commission; as such he wrote ‘Appendix A: Stained Glass’ for the official report.16 After this experience, Art Deco tendencies began to show in his work, which although remaining decidedly Gothic in overall nature, now took on a new degree of geometric and linear design (FIG. 1 at Bottom). In an article originally printed in the New York Times Magazine, Connick recorded that the 1925 Paris Exposition ‘revealed an exuberant spirit in all crafts’ and the ‘experiments shown there shocked many designers and craftsmen from the orthodox shops and factories of America.’17 Connick verbally illustrated the glass showcased, giving us an idea of the ‘bizarre arrangement in iron, lead and glass in chunks and in bulging built-out sections that marks the doorway of the Lafayette pavilion’ (perhaps an early version of dalle de verre) which can be seen in the Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs’ photograph (VIEW HERE).18 Connick also described the ‘cubist decoration’ of the building devoted to Transport and Tourism, and the unsuccessful enamelled windows that ‘have already begun to peel off,’ after only one year in the church at Rancy.19 Despite a previous dislike for etching and cutting on plate glass, Connick expressed astonishment at the success of the examples provided by the French artists.20 It was with this new style of etched plate glass fresh in his mind that Connick went into his commission for the storefront of the new building for Boston furriers, Lamson & Hubbard. The Lamson & Hubbard Storefront Although Connick was, arguably, influenced by Art Deco in his other windows of the period, such as the Christian Epic windows in Princeton University’s chapel (FIG. 1 at Bottom) and the windows of St Gabriel’s Catholic Church in Washington, DC, his embrace of etched glass for this commission was a strong departure. Connick Studios embarked on the Lamson & Hubbard storefront commission in 1929 after multiple requests for ‘the type of ornamental glass which has recently been developed in France and in this Country; that is, the method of etching or chipping patterns on plate glass, and these patterns possibly enriched with gold, silver or color.’21 For the storefront, Connick designed the windows and made cartoons, and collaborated with the Eny Art Glass Company of New York City who manufactured the etched windows (Image to come).22 Art Deco sympathies are evident. The bold, angular lines and stylised imagery seen throughout the Lamson & Hubbard storefront represent this new type of design (Image to come). An Ocelot is shown crouching in profile at the center of a cartouche, which in turn is centered in a square panel of glass (VIEW HERE). The strong geometric patterns in the sawtooth border of the square panel, the bold brick-like pattern surrounding the ocelot, and the modified fret or key pattern on which the ocelot stands all reveal the impact of Art Deco, and the strong outlines and stylisation add to the flattened appearance of this etched window. The minimal color palette – the majority of the window is colourless – along with the wide white borders, recalls the new type of etched glass shown in Paris. Based on letters from Connick to the Eny Art Glass Company and Peter Andre, Inc., it is evident that he likely found his inspiration in the etched glass windows he had seen at the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts.23 A comparison with The Leopard, a window created by Gaëtan Jeannin in collaboration with Eric Bagge, reveals what may be seen as a direct influence on the storefront design (VIEW HERE, PAGE 26 OF TEXT).24 Connick himself acknowledged that the commission was ‘somewhat of an experiment.’25 The use of plate glass and etching and the collaboration with an outside company were all unusual for the Studio. Despite the challenges required, and the multiple changes and improvements needed to adapt to the new medium, Connick recounted that he was ‘beginning to see excellent possibilities in such work, and even if this commission should be abandoned, I shall undertake other things of the sort for sympathetic clients.’26 Dalle de verre innovations and exhibitions of the 1930s During the 1920s and ’30s, French glass artists established an innovative technique in glass making, soon known as dalle de verre, which diverged from contemporary methods of stained glass production based on traditional techniques. In this method, chunks of glass – known as dalles or slabs – were inset in cement and strengthened with a wire framework. It is worth noting that this type of architectural glazing resembles an older method of insetting thick chunks of glass in a geometric stone framework, as used throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East; it is possible that the French artists were aware of this historic type of glazing.27 The 1937 Paris World’s Fair was the first time that dalle de verre was exhibited to the public on a large scale, the French Pavilion of stained glass displaying the process of construction and the finest examples of this new medium.28 According to American stained glass artist Joseph Reynolds, such windows were controversial in Paris, polarising opinion between the Academy and those who supported the contemporary style.29 Dalle de verre windows made for the Cathedral of Notre Dame were included in the Roman Catholic Pavilion. Despite their modernity, they had lancets filled in the traditional Gothic manner with single figures of saints surrounded by a wide border.30 Interestingly, the Egyptian Pavilion also included examples of dalle de verre. Although the United States participated this time in the exhibition, their pavilion was poorly designed and crowded. Connick himself included seven medallion windows, including two replicas from the Christian Epic windows at Princeton University Chapel, and five made from glass salvaged from the area around the closed Boston & Sandwich Glass Company.31 In 1939, dalle de verre windows made their way to North America in the work of French-born artist Auguste Labouret. His window One of the Magi, made in 1936, was shown at the New York World’s Fair.32 He also installed what is thought to be the first such window on the continent at the important Shrine of Saint Anne de Beaupré in Quebec, Canada, to which he would eventually contribute over two hundred windows. Labouret was an early pioneer of dalle de verre in France, helping to develop the technique in the early 1930s.33 Saint George Connick spent a considerable amount of time travelling throughout the United States for commissions and also around Europe studying medieval stained glass. He attended and participated in exhibitions and World’s Fairs, and consequently was well aware of any innovation in his craft. It is therefore probable that Connick knew of dalle de verre as both an ancient and modern technique before the 1937 World’s Fair, where he certainly observed the examples on show. In a 1993 interview, Orin E. Skinner, Connick’s ‘left-handed right-hand man,’ said that Connick Studios did some work in dalle de verre but that they did not particularly like it.34 Marilyn B. Justice, President of The Charles J. Connick Stained Glass Foundation, who was present at this interview, agreed but added that the door of the studio actually had dalle de verre glass inset in it.35 The Charles J. Connick Stained Glass Foundation Collection at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology includes a panel reminiscent of dalle de verre (VIEW HERE). The Saint George panel (c.1930-1940) is not known to have been a commission – and based on its small size, just over two feet at the longest – it was probably made as a sample panel and is markedly stylised in its design. It illustrates Saint George sitting atop a white horse, his helmeted head low against the horse’s neck with a red cloak billowing out behind him. In his hand he holds a white shield with a red cross. Entwined beneath the horse’s legs is a dragon, almost imperceptible in its abstraction. All the figures are seen in profile. The leadlines are extremely thick, and opaque black paint visually increases their width. Although the glass is just a flat sheet, it is painted with vitreous paint so as to appear faceted. This panel was apparently an early experiment to create the look of faceted glass (or was it perhaps a reaction against faceted glass?). Skinner’s admission that they did not like the medium may have prompted the mimicking of the style in a medium that the Studio preferred. Whatever the purpose of the St George panel, it is clear that Connick followed innovations in his craft and did not balk at trying them in his own work. Plexiglas and World War II The nineteenth century saw the creation of the first plastics, namely celluloid, Bakelite and a large number of chemically similar products. These plastics could only be moulded one time and were visually opaque.36 Thus the invention of acrylic glass, given the brand names ‘Plexiglas’ by Röhm & Haas Company and ‘Lucite’ by their competitor DuPont Lucite, was revolutionary. Acrylic glass is colourless and transparent, can be made into large sheets and bent into any shape – and importantly, it can be remoulded after being formed.37 In 1939, Röhm & Haas Company had an exhibit designed to showcase Plexiglas and also Crystallite acrylic plastic (the powdered version suitable for moulding), at the World’s Fair in New York.38 The Herman Miller Furniture Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan, included a Plexiglas and tubular steel chair at the fair, the epitome of modern design.39 Plexiglas was quickly embraced by the World War II war effort as the perfect solution for shatterproof windows, canopies, bomber noses and gun turrets in the new high-altitude military aircraft.40 Post-war, Crystallite became the preferred material for headlights, turn signals and taillights for automobiles and Plexiglas became well known through backlit signs, like those of Shell gas-stations, McDonald’s, jukebox windows and movie marquees.41 New England Fantasy During World War II, rationing of everyday materials became the norm and the rationing of metals, namely lead, directly affected Connick Studios. In a 1943 letter to the Bureau of Construction and War Production Board Connick petitioned for the right to use lead that the Studio already owned.42 The lengths to which he had to go to use his own lead, plus the fact that the studio’s younger staff were absorbed by the war effort, leads one to wonder how the Connick studio’s output was affected.43 In fact the lead shortage, coupled with Connick’s own inclinations towards innovation and modernity, spurred him on to try his own experiments in plastic.44 According to Orin E. Skinner, Connick was ‘among the first to try ‘gelva,’ and others of the earliest plastics.’45 Experiments, such as plastic curtain pulls and plastic and glass buttons, culminated in the creation of a full size window, the New England Fantasy (FIG. 2 at Bottom),46 made for exhibition at the Contemporary American Industrial Art Exhibition of 1940 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.47 Skinner later related that the window was ‘a panel of colorful glass imbedded in one of the synthetic resins in sections glazed with zinc cames.'48 The panel was heralded by Glass Digest as a ‘new type of glass, quite different from anything that has been done before,’ and was described by Connick as a ‘Coloralight Mosaic’, with its ‘patent pending’.49 Although the New England Fantasy is not a dalle de verre window as such, it is worth noting that its marriage of acrylic resin and chunks of glass predates by almost twenty years the major technical innovation of epoxy resin as the material to hold the slabs of glass together. Robert R. Benes, working with Jacoby and Frei Studios in New Orleans, is credited with the formulation of a special blend of epoxy to replace the cement in dalle de verre windows around 1960.50 Connick’s brilliant mosaic used the new materials to illustrate Leonora Speyer’s ballad about ‘Old Doc Higgins’, who shot a mermaid. It was representative, according to Connick, ‘of the contests constantly going on between the literal- minded folks and the creatures of the imagination.’51 Doc Higgins inhabits the right side of the panel with the mermaid on the left, both figures facing each other in profile. Waves curl around the mermaid’s tail and the focal point of the window is a brilliant sun at the apex. The sun’s rays project down across the window in angular paths of saturated yellows, oranges and pinks. The colorless transparent quality of the acrylic added to the glowing quality of the panel, for which a light-box with fluorescent illumination was constructed.52 The desire to illuminate with artificial light was part of Connick’s ambition to bring colour and light beyond cathedral walls into factories, offices, schools and any space where it could best serve the public (FIG. 3 at Bottom). In addition to the New England Fantasy window, Connick made a number of ‘Coloralight Medallionets’ which were comprised of the ‘scraps of glass we are using in our great windows, and a new plastic material that is very light and very durable so these little Medallionets can sing forth their messages in the light almost anywhere.’53 An example of such a ‘medallionet’ has been found in the Charles Connick Foundation collection (Image to come). Its misshapen form suggests the sensitivity of the materials to overly warm conditions. In addition to this small example, two others are known from letters. Connick gifted one of them to Florence W. Foss of South Hadley, Massachusetts, who assisted him with a commission at Mount Holyoke College, and the other to Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings.54 He also made Kodachrome photographs of the New England Fantasy window to create Christmas cards that further publicised his new invention.55 A Modern Gothicist Charles Connick is considered by many to be the most important Modern Gothic stained glass artist of the twentieth century. In fact, the depth of his knowledge of stained glass, his passion for the creation of stained glass windows and for educating the public through lectures and writings, helped to define the Modern Gothic style of stained glass early in the century. As scholars Peter Cormack and Albert Tannler have pointed out, this was in sharp contrast to the prevailing influence of opalescent windows in America as practiced by Tiffany and La Farge et al.56 Despite Connick’s dedication to the techniques and materials of medieval stained glass, as these authorities have noted, he was not a historicist or a copyist. His drive for constant learning and innovation and his ambitious creativity is apparent through the evolution of his style. This is evident in numerous windows, many considered masterpieces of their time. The case studies presented here further illustrate some of the more unusual examples of Connick’s desire to embrace contemporary trends and experiments, letting nothing stand in his way of creating the very best stained glass of which he was capable. Connick may have been a Gothicist in spirit but he was unquestionably also a Modernist. Perpetual modernness is the measure of merit in every work of art. Charles J. Connick ________ NOTES 1 Joan Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years: Life before Boston,’ Connick Windows (Boston: Charles J. Connick Foundation, February 2000), http://www.cjconnick.org/newsletters/February2000.html; Albert J. Tannler ‘Edward Burne- Jones and William Morris in the United States: A Study of Influence’ The Journal of Stained Glass, Burne Jones-Special Issue 35 (2012), includes analysis of Charles Connick pp. 53-57. 2 Joan Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years’, Connick Windows. 3 Charles J. Connick, Adventures in Light and Color (New York: Random House, 1937), 4; Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years’. 4 Connick, Adventures in Light and Color, 4. 5 Ibid. 6 Ibid. 7 Ibid. 8 Ibid. 9 Gaul, ‘Connick’s Pittsburgh Years’; Noreen O’Gara, ‘Retrospective Charles J. Connick,’ Stained Glass Quarterly (Spring 1987): 45; Peter Cormack, ‘Glazing “with Careless Care” Charles J. Connick and the Arts & Crafts Philosophy of Stained Glass,’ The Journal of Stained Glass 28 (2004): 82. 10 Ibid. 11 O’Gara, ‘Retrospective’, 45. 12 Ibid. 13 Ibid. 14 Ibid. 15 ‘History of the Connick Studio’, The Charles J. Connick Foundation, http://www.cjconnick.org/studio-history/. 16 Charles J. Connick, ‘Appendix A: Stained Glass.’ Report of Commission appointed by the Secretary of Commerce to visit and report upon the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Art in Paris, 1925. 17 Charles J. Connick, ‘Modern Stained Glass at the Paris Exhibition, 1925,’ The Journal of Stained Glass 2 (1927), 12. 18 Connick, ‘Appendix A.’ 19 Ibid. 20 Connick, ‘Modern Stained Glass,’ 16. 21 Letters to Peter Andre, Inc. and the Eny Art Glass Company, 19 March 1929, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 22 Memos, 16 November 1929 and 3 December 1929, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 23 Letters to Peter Andre, Inc. and the Eny Art Glass Company, 19 March 1929. 24 Jacques Gruber, Le Vitrail a L’Exposition Internationale Des Arts Decoratifs Paris 1925 (Paris, France: Editions Charles Moreau, 1926), fig. 26. 25 Letter to Theophile Schneider, 8 May 1930, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 26 Letter to Theophile Schneider, 30 July 1929, Lamson & Hubbard, Boston, Mass. files, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 27 ‘History of Stained Glass’ Stained Glass Association of America. Accessed 12 May 2014, http://stainedglass.org/?page_id=169 28 ‘Modern Stained Glass at Paris Exposition Discussed by Joseph G. Reynolds, R. Boston Craftsman,’ Reel 3, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 29 Ibid. 30 Ibid. 31 Glass Digest (1937), Charles J. Connick file, Rakow Library, Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York. 32 ‘History of Stained Glass’, Stained Glass Association of America. 33 Ibid; ‘Stained Glass’, Sanctuaries-Shrine Sainte-Anne De-Beaupré. Accessed 12 May 2014. http://www.sanctuairesainteanne.org/index.php?option=com_zoo&view=item&layout=item&It emid=201&lang=en 34 Richard Hoover, ‘Behind the Scenes: Conversing About Stained Glass with Orin E. Skinner,’ Stained Glass 98 (Summer 1993), 109. 35 Ibid. 36 Jason T. Busch and Catherine L. Futter, Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs, 1851-1939 (New York: Skira Rizzoli, 2012), 30. 37 Ibid. 38 Ibid. 39 Ibid. 40 Ibid., 42. 41 Busch and Futter, 32; also ‘Leading the Way From 1933 to 2008,’ Altuglas International Arkema Group, accessed 24 March 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20120905160256/http://www.plexiglas.com/home/aboutus/timeline _content 42 Letter to the Bureau of Construction, 10 June 1943, Church Street Church, Knoxville, Tennessee file, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. 43 Ibid. 44 Virginia S. Bright, ‘Interview with Charles J. Connick May 10, 1945,’ Reel 2, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 45 Orin E. Skinner, ‘An Autobiography,’ Stained Glass 72 (1977-78), 234; Orin E. Skinner, ‘Connick in Retrospect,’ Stained Glass (Spring 1975), 18. 46 Skinner, ‘Connick in Retrospect,’ 18. 47 ‘ “New England Fantasy” Coloralight Mosaic by Connick of Boston,’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gelva, New England Fantasy, New York City file, Charles J. Connick and Connick Associates Archives, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library, Boston, MA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art Contemporary American Industrial Art 1940, 15th Exhibition (29 April 29-15 September 1940), 25. 48 Skinner, ‘Connick in Retrospect,’ 18. 49 Glass Digest (June 1940), Charles J. Connick file, Rakow Library, Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York, ‘‘New England Fantasy’ Coloralight Mosaic by Connick of Boston,’ 25. 50 ‘History of Stained Glass’, Stained Glass Association of America; ‘History of Jacoby Stained Glass Studios, Inc.,’ Jacoby Art Glass Company, St Louis, MO, accessed 27 March 2013, http://tropicalsails.com/jacobyoppliger/; Oppliger, William, and Stephen Frei, ‘Jacoby Art Glass Company’, ‘Christ Church Bluefield,’ accessed 13 May 2014, http://www.cecblf.org/jacoby.html 51 ‘‘New England Fantasy’ Coloralight Mosaic by Connick of Boston,’; letter to Mr and Mrs Fuller, 20 December 1941, Reel 1, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 52 Ibid. 53 Letter to Miss Foss, 10 April 1940; letter to Mr and Mrs Fuller, 20 December 1941, Reel 1, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 54 Ibid. 55 Letter to Brother Yeomans, 20 December 1941; letter to Mr and Mrs Fuller, 20 December 1941, Reel 1, Charles J. Connick Papers, 1901-1949, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. 56 Peter Cormack, ‘Glazing “with Careless Care” Charles J. Connick and the Arts & Crafts Philosophy of Stained Glass,’ JSG 28 (2004): 79-94; Albert J. Tannler, Charles J. Connick: His Windows in and Near Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation, 2008). This article was published by the Journal of Stained Glass, the scholarly journal of the British Society of Master Glass Painters, to whom I am most grateful. |

ArchivesSamantha

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed